To pick up where we left off, this article explores the concept of “hard-to-value intangibles” and a court case dealing with intangible assets.

As new precedents develop, the competent authorities seek to assess risks inherent in intangibles transactions, as well as drawing up guidelines and recommendations that will help tax authorities identify potentially risky related-party transactions and will help taxpayers avoid mistakes in making new arrangements and carrying out new transactions.

In June 2018 the OECD published BEPS Action 8 as guidance for tax authorities in applying the concept of hard-to-value intangibles.

The term “hard-to-value intangibles” refers to intangibles or rights to such assets that have no reliable comparables at the time of transfer between related companies, where forecasts of future cash flows or income expected from the intangible at the time of transaction or assumptions used in valuing the intangible are so unclear that it is difficult at the time of transaction to predict the ultimate success of the intangible.

Those could be intangibles that –

A risk associated with a hard-to-value intangible arises, for instance, where an entity transfers an intangible at an early stage of development to a related party, sets a fee that fails to reflect the value of the intangible at the time of transfer, and later claims that it was not possible to predict with certainty the success of the intangible at the time of transfer. So the taxpayer claims that the difference between the ex-ante and the ex-post value of the intangible is attributable to trends that are more favourable than expected.

The last decade has seen an increase in lawsuits over intangibles transactions. Since resultant tax assessments can be huge, it is worth paying attention to intangibles transactions.

Below we will explore the Nike/Converse court case, in which royalties for the grant of rights to use intangibles were exploited as a means of shifting profits.

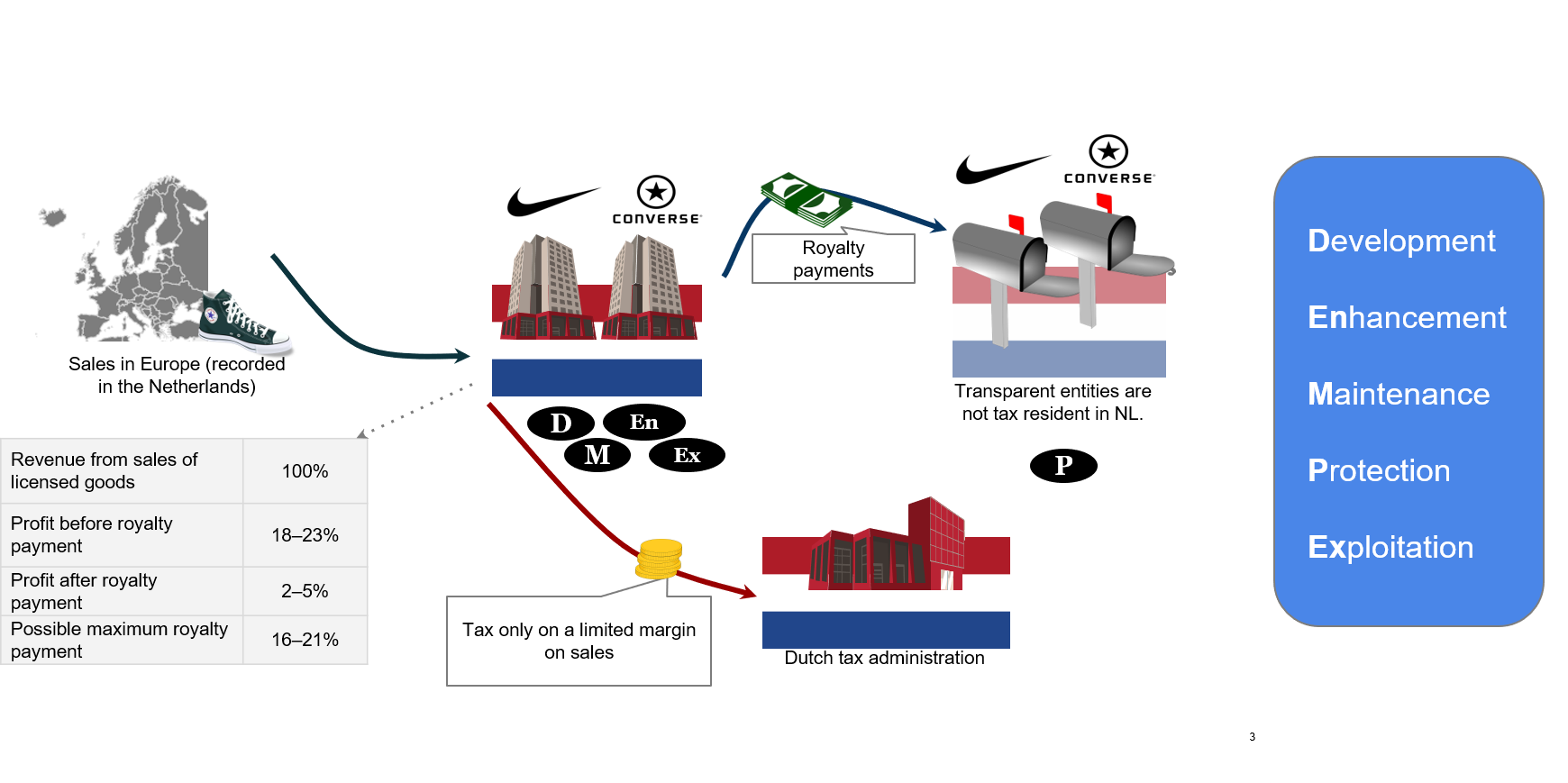

Nike is a US group of companies that has included the Converse group since the early 2000s. The group has set up an arrangement in Europe owning a number of Dutch entities, including two Nike group entities involved in this lawsuit in the Netherlands: Nike and Converse. Those entities perform a wholesale distributor’s functions, i.e. product design, sales, pricing policy, inventory management, customer service, and marketing on the European market. The two companies employ over 1,000 workers. An evaluation of their activities according to the DEMPE concept we mentioned in our earlier article shows that the wholesale entities were involved in performing four DEMPE functions associated with developing intangibles: development, enhancement, maintenance, and exploitation. The two entities hold licences to use trademarks and patents for Nike and Converse products in the European region for which royalties are paid.

The licensors receiving royalties are two other group entities in the Netherlands owning trademarks and patents in the European region. An evaluation of their activities according to DEMPE shows that the intangibles owners performed only one DEMPE function associated with protecting the intangibles. The licensors are registered as limited partnerships, which are treated as transparent entities for Dutch tax purposes and therefore exempt from corporate income tax. Those entities have no employees and conduct no business so they can be considered shell entities.

The picture below shows the arrangement of intangibles transactions:

As to royalties, the group has determined that its Dutch wholesale entities must earn a 2–5% margin for their activities, with any excess being treated as royalties.

As to royalties, the group has determined that its Dutch wholesale entities must earn a 2–5% margin for their activities, with any excess being treated as royalties.

This mechanism for setting royalties was approved by the Dutch tax authority, who entered into five advance pricing agreements with the Nike group over a ten-year period.

Because of concerns about the agreed royalties failing to reflect the economic reality, the European Commission is now checking whether the Dutch tax authority has given an unfair advantage – state aid – to the Nike group compared to the competition.

An assessment of the DEMPE functions found that the royalties are not consistent with the parties’ contribution to creating the value of the intangibles. Accordingly, the shell entities were not entitled to the high level of royalties from the wholesale entities.

Although the final decision in this lawsuit is still pending, we can see that the European Commission as well as tax authorities are monitoring internal arrangements in multinational enterprise groups and evaluating related-party transactions, especially more risky transactions, for instance, those involving intangibles.

To wrap up this topic, it is important to note that the characteristics and risk levels of intangibles transactions vary widely. So, when it comes to planning or taking part in intangibles transactions over a long period, we recommend annually evaluating the prices applied in those transactions and preparing documentation that will help the taxpayer show that the transactions have no transfer pricing risk.

If you have any comments on this article please email them to lv_mindlink@pwc.com

Ask questionAs the tax system evolves, the regulatory authorities have been rearranging their priorities around transfer pricing risks and focusing on increasingly complex cases in recent years. The transfer pricing aspects of intangible assets are climbing up the agenda, so we will be posting a few articles to explain the significance of related-party transactions involving the use of intangibles, as well as looking at transfer pricing trends, common risks, and relevant case law.

The legal form, meaning the contract between related parties and its provisions, has always been among the factors that come into play when assessing whether prices applied in controlled transactions are arm’s length. This article discusses why the legal form of a transaction is important, looks at a common approach to preparing intragroup contracts, and explores some rules that should be followed when drafting those contracts to mitigate transfer pricing risks.

Section 15.2 of the Taxes and Duties Act requires a taxpayer to meet requirements for the timeliness of information included in their transfer pricing (“TP”) documentation and for regular updates to reflect the present situation. During a period of calm in preparing and filing TP documentation, we asked the State Revenue Service (“SRS”) to answer some confusing questions about updating comparable data and revising financial data, including the scope for taking the roll forward approach.

We use cookies to make our site work well for you and so we can continually improve it. The cookies that keep the site functioning are always on. We use analytics and marketing cookies to help us understand what content is of most interest and to personalise your user experience.

It’s your choice to accept these or not. You can either click the 'I accept all’ button below or use the switches to choose and save your choices.

For detailed information on how we use cookies and other tracking technologies, please visit our cookies information page.

These cookies are necessary for the website to operate. Our website cannot function without these cookies and they can only be disabled by changing your browser preferences.

These cookies allow us to measure and report on website activity by tracking page visits, visitor locations and how visitors move around the site. The information collected does not directly identify visitors. We drop these cookies and use Adobe to help us analyse the data.

These cookies help us provide you with personalised and relevant services or advertising, and track the effectiveness of our digital marketing activities.