Wrapping up our previous article “Unified approach to addressing tax challenges in digital economy,” this article explores the OECD’s proposals for international taxation rules within Pillar Two.

Background

Within the Programme of Work to Develop a Consensus Solution to the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy, the OECD has released a public consultation document on Pillar Two (aka the “GloBE” proposal), which calls for the development of a coordinated set of rules to address ongoing risks from structures that allow MNEs to shift profit to jurisdictions where they attract a very low tax or no tax at all. Pillar Two can be seen as a basis for introducing a minimum tax rate.

The OECD’s proposals

To tackle the remaining instances of international profit shifting to no tax or low tax jurisdictions, the OECD proposes a set of four rules to be aligned with each other. The rules are based on a minimum effective rate of tax payable by each multinational company, ignoring the tax rules and benefits provided by the countries where the multinational is operating. The four rules are as follows:

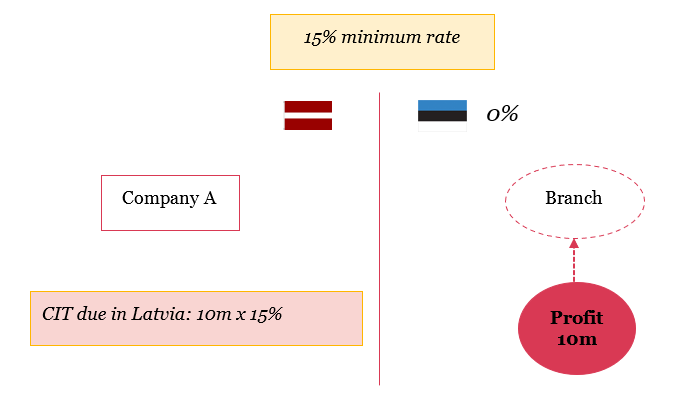

The “income inclusion” rule would tax the income of a foreign branch or a controlled entity if that income was taxed at an effective rate below the minimum rate (please see an example below):

The branch of Company A operates in Estonia. Under the Estonian rules, if the branch does not distribute the profit, no corporate income tax (“CIT”) is due. Thus, applying the “income inclusion” rule means that Company A will have to pay Latvian CIT on the income gained in Estonia by applying the minimum rate. Although the minimum rate has yet to be proposed by the OECD, all examples posted by the OECD within Pillar Two contain a minimum rate of 15%.

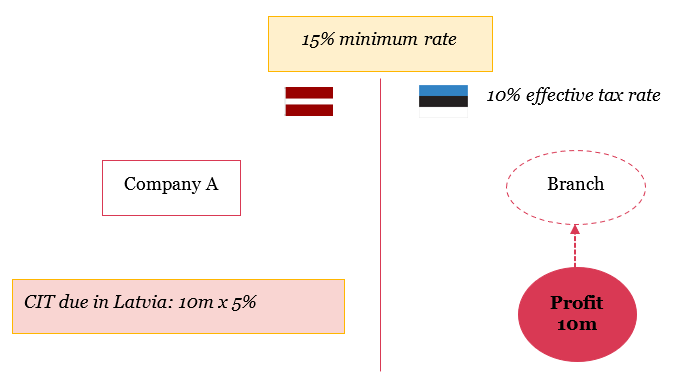

The “switchover” rule is to be inserted into double tax treaties to permit the residence jurisdiction to switch from an exemption to a credit method where the profits attributable to a permanent establishment (PE) or derived from real estate (which is not part of that PE) are subject to an effective rate below the minimum rate (please see an example below):

If the branch jurisdiction has taxed the income at an effective tax rate of 10%, which is below the 15% minimum, the current provisions of the Latvian CIT Act that exclude PE profits from the Latvian company’s tax base are ignored, and the credit replaces the exemption method. So Company A should pay in Latvia the difference between the minimum rate and the rate of CIT paid in Estonia (i.e. 15% – 10% = 5% CIT to be paid in Latvia on the income gained by Company A in Estonia).

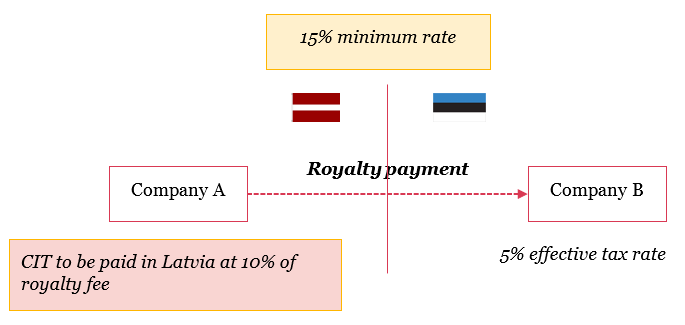

The “undertaxed payment” rule would operate by denying a tax deduction or imposing a source-based tax (including withholding tax) on a payment made to a related party that was not taxed at or above the minimum rate:

Company A makes a royalty payment to a related party established abroad. Under the tax rules of the residence country of Company B, income from intangible assets attracts a 5% CIT, which is less than the minimum rate of 15%. The “undertaxed payment” rule would allow Country A to impose a source-based tax on the royalty payment equal to the difference between the minimum rate and the tax paid by Company B (i.e. 15% – 5% = 10% CIT to be paid in Latvia by Company A).

The “subject to tax” rule would complement the “undertaxed payment” rule by subjecting a payment to withholding or other taxes at source and adjusting the eligibility for treaty benefits on certain items of income where the payment is not taxed at the minimum rate. Thus, by applying this rule to the previous example, the royalty payment made by Company A to B will attract a 10% Latvian withholding tax despite the Latvia–Estonia double tax treaty allowing this tax to be reduced to 5%. In this case the treaty benefits will not be available.

Conclusion

One of the most important and immediately interesting questions for most taxpayers is whether their group will fall within the scope of Pillar Two. Unfortunately, while the OECD notes that there may be exemptions and invites comments, there is no clear guidance as yet on what those exemptions might be. What is clear, however, is that Pillar Two is not restricted to digital businesses.

Of additional interest will be the question of how many and which countries will adopt the OECD Pillar Two recommendations once they are finalised. The latest OECD comment suggests that while the OECD is hoping for a widespread adoption of Pillar One, they do not expect the adoption of Pillar Two to be so extensive.

As the OECD notes, the Pillar Two recommendations represent a substantial change to the international tax architecture, and as with Pillar One, the OECD recommendations may be widely debated.