Zane Smutova

Senior Manager, Transfer Pricing, PwC Latvia

Liga Dobre-Jakubone

Manager, Transfer Pricing, PwC Latvia

Some of the substantial changes made to Latvia’s transfer pricing (TP) rules effective from 1 January 2018 prescribe how corporate income tax (CIT) payers should identify related parties before reporting and analysing their mutual transactions in their TP documentation. This article explores whether fellow subsidiaries are treated as related parties and offers a practical example of identifying this status.

Rules on related parties

The easiest way two companies can become related parties is by meeting the direct shareholding condition, i.e. one company’s share in the other is 20% and more.

It may be far more difficult to identify related parties where two companies are not linked through a direct shareholding but are controlled by the same entity or group, i.e. they are fellow subsidiaries.

This situation was covered by the old CIT Act, which required taxpayers to prepare specified details of transactions between related parties if they are members of a group (including one entity with a direct or indirect shareholding of at least 90%), making it clear that transactions between fellow subsidiaries are treated as related-party transactions. The new CIT Act no longer refers to a group of companies, and the Taxes and Duties Act is silent as to whether transactions between fellow subsidiaries are treated as related-party transactions. In other words, there is no specific guidance as to whether such companies are treated as related parties and whether their transactions should also be examined for TP purposes.

According to a theoretical opinion issued by the State Revenue Service (SRS), the definition given by any particular subsection of section 1 of the Taxes and Duties Act is not directly applicable in identifying related parties, so this relationship should be assessed by combining those subsections instead of considering each in isolation.

Since the current rules are silent as to whether transactions between fellow subsidiaries are treated as related-party transactions, each particular relationship with group companies should be assessed on its own merits.

A practical example of identifying related parties

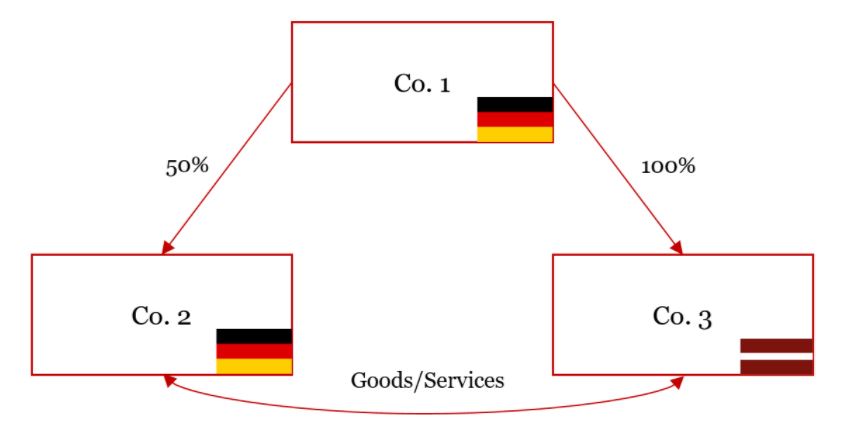

A German company (Co.1) has a 50% stake in another German company (Co.2) and wholly owns a Latvian company (Co.3). Both Co.2 and Co.3 are run by a board of several members, each authorised to act for the company separately and two of them sitting on the board of both companies. Co.2 and Co.3 made mutual transactions in 2018.

Assessing this situation leads to the following conclusions:

- Co.2 and Co.3 are related parties under subsection (f) of section 1(18) of the Taxes and Duties Act because the same board has a majority in both companies (the same persons have a majority vote on the boards through being authorised to act for the company separately).

- If the majority vote condition is not satisfied, then Co.2 and Co.3 could be treated as related parties by combining subsection (a), which mentions the parent and a subsidiary, and subsection (b), which mentions one company’s stake in the other exceeding 20%, of section 1(18) of the Taxes and Duties Act.

It is important to note that the relationship with a foreign company may also be assessed under Latvia’s double tax treaty (usually article 9), which may provide that related companies exist where one country’s company directly or indirectly participates in the management or control of the other country’s company or owns some of its share capital.

Accordingly, Co.2 and Co.3 are treated as related companies because Co.1 owns shares in both.